Claudia von Alemann

Lire la suiteThe history of 19th century feminism looms large in her work, which includes one book and two films devoted to the topic. However, like Flora Tristan—who believed that the emancipation of the working class relied on the emancipation of women—her films address patriarchy and capitalism in the present tense, tackling both topics head-on in the 1972 film The Point Is to Change It, as well as in Nuits claires and in the films she shot in Thuringia after the fall of the wall.

After Nuits claires, the films shot in her home region drew on her family’s story as well as her own, all the while throwing light on the blind spots of German history. From that moment on, her films took a more distinctively biographical turn. They suggest that you cannot speak about others without speaking about yourself, and that you cannot talk about history without delving into your own past.

In Feminist Worldmaking and the Moving Image, the catalogue of “No master territories[1]”, a 1976 piece by Claudia von Alemann examines the word “collective”, framing it as a powerful force for thought, resistance, and action. The collective is one of the arguments driving von Alemann’s desire to film and her commitment as a feminist filmmaker. If the intimate is political, then shared experience and the politics of friendship, or sisterhood as we might call it today—as portrayed in The Next Century Will Be Ours and in Nuits claires—are integral to creation. Her latest film, devoted to her friend the photographer Abisag Tüllman, is a graceful expression of this.

Catherine Bizern

[1] The exhibition, curated by Hila Peleg and Erika Balsom, was on show at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt, in Berlin, and at the Warsaw Museum of Modern Art in 2023.

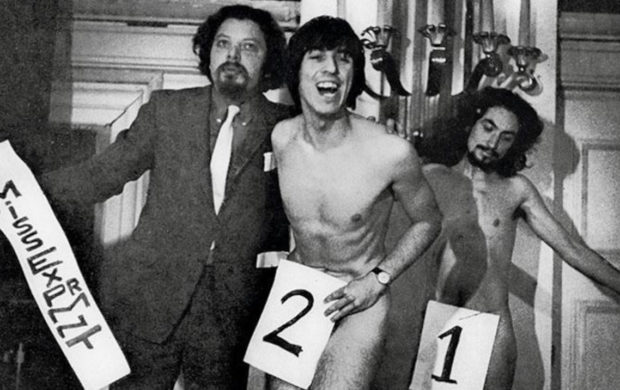

Exprmtl 4 knokke

Blind Spot

Lichte Nächte

Kathleen und Eldridge Cleaver in Algier

Die Frau mit der Kamera